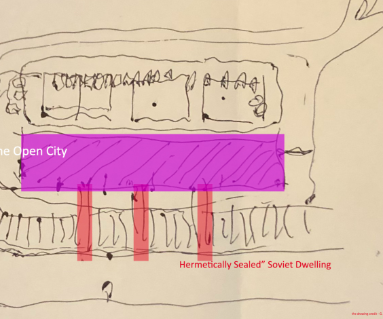

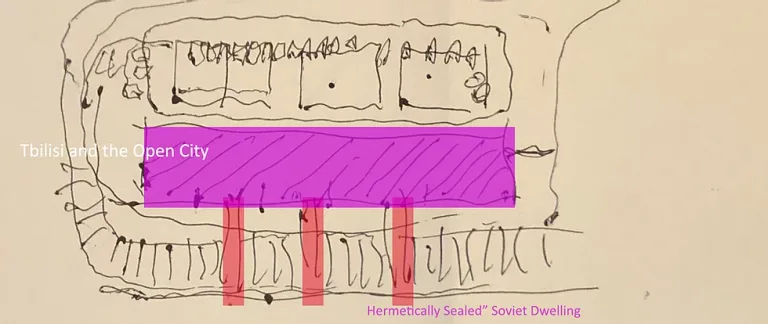

Ia Kupatadze “Tbilisi and the Open City ‘Hermetically Sealed’ Soviet Dwelling”

The city, with its physical forms and social relationships, forms a structure – a system that serves its inhabitants. It is a place that gives people the ability to create formal and informal spaces, further adjusts and re-develops based on the inhabitants’ needs. It can be described as part of ‘a social process’ (Tonkiss, 2013, p. 1) in which the relationship between ‘the past, present, and the possible cannot be separated.’ (Lefebvre, 1996, p. 148).

Cities can be a closed or an open system. In the closed city system people are unable to make changes, these cities are built with a top-down approach, pre-planned by authorities and professionals. Closed city system is standardized, regulated, divided into zones where ‘everything fits properly’, with the notion that the planning will ensure its cleanliness, safety, and efficiency. On the other hand, an open city system is a bottom-up approach to city planning, in which people have an opportunity to take part in the city formation processes by active interventions. Diversity and density, the interaction of different people, street life, and the way people dwell and change create, as Jane Jacobs believes, an open city system (Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities, 2016). An American sociologist, Richard Sennett draws a parallel between these two systems, describing the closed system as a “harmonious equilibrium”, and t he open system as an “unstable evolution.” He believes that a closed system has paralyzed urbanism, while an open system might free it. (Sennett, The Public Realm, 2010, p. 261) Allowing more uncertainty, chaos, and freedom, ‘the open city system cannot be designed’ (Christiaanse, 2009, p. 36) with a set of rules that help to construct the place (Eisinger, 2009, p. 49).It is a process that must morph together with its dwellers. R. Sennett describes the closed system as “overdetermined, balanced, integrated, a linear approach” and the open system as “incomplete, errant, conflictual, non-linear approach” (Sennett, The Open City, 2017, p. 14)

‘Cities play[ed] the central role in Soviet life’ (Morton & Stuart, 1984, p. X) and their physical characteristics were to be ideologically attuned to the communist doctrine. As such, Soviet cities were almost hermetically closed systems. While the Soviet Union was formed by numerous autonomous republics, with their national and/or regional histories and, consequently, identities, the decision-making process about the planning of the cities everywhere was in the hands of the authorities in Moscow, who used standardized and restricted doctrines without taking into consideration the specificities of the particular society and culture where the city was to be developed. They never gave people living in fifteen different republics, with the diversity of cultural backgrounds and geographic locations, the ability to take part in the city or neighbourhood formation processes, to initiate any changes, and to create either formal or informal settings within the city or even in small neighbourhoods. It was a political and ideological process (Dehaan, 2013, p. 11), where the cities became the political and ideological battlegrounds, rather than being entities that supported the social structures and everyday lives of its inhabitants. These cities were never thought of as “[a] set of elements that create a certain system that co-operates or works together somehow’ (Alexander, 1965, p. 2). Natural city formation processes were fully rejected by the Soviet authorities, instead focusing on structured and planned-out ones, fully divided and organized by functions. Planners and architects had no right to make suggestions nor corrections, serving only “as mediators of ideological discourse” (Dehaan, 2013, p. 12). The housing units were standardized ideological objects, “by which formation of a new soviet person was envisioned” (Khazanov, 1980, p. 27).

In order to draw a parallel between the closed city system and the Soviet city planning characteristics, I would like to analyse one particular housing unit, where architecture and its location played an important role in urban setting formation processes. I believe that the urban form of the unit describes well the influence of the Soviet ideology – the communist doctrine. By studying the building – its architecture and urbanity, I inquire into the reasons why this unique architectural form stands alone today as an urban structure with big open space without public access; why the form (architecture) and its surroundings did not change and evolve with time, continuing to be ‘hermetically sealed’ in the centre of the city that has been radically altered in recent decades due to political, economic, and financial changes.

The project was funded by Tbilisi Architectural Biennial 2020